Markets are showing mounting concern about Sri Lanka’s ability to manage debt loads, amid financial deterioration that sparked a downgrade deeper into junk Friday.

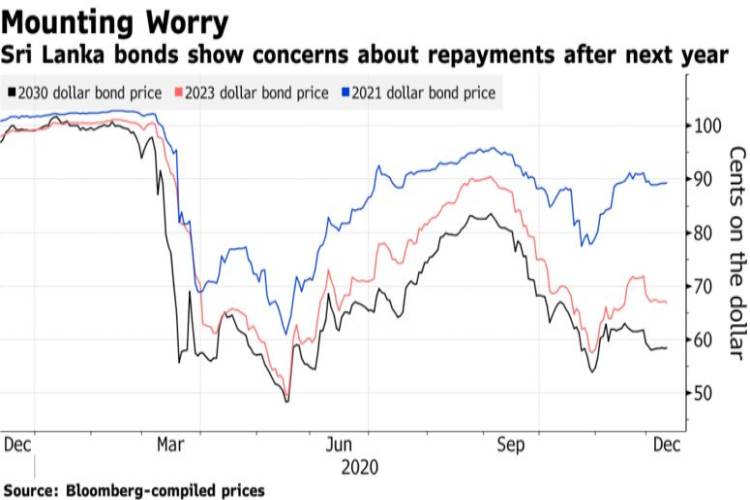

Prices of the country’s dollar bonds show that while traders expect securities next year to be repaid, they’re increasingly uneasy about dwindling cash reserves for debt bills down the line.

Notes due in 2021 are indicated at about 88 cents on the dollar, according to prices compiled by Bloomberg. That’s a level that shows some misgivings yet not alarm. But securities maturing in 2023 are at about 66 cents, while it’s even worse for ones due 2030 at 57 cents.

“The pricing of longer-dated bonds reflects higher risks, on the back of a projected decrease in foreign exchange reserves to repay the 2021 bonds,” said Ek Pon Tay, senior portfolio manager for emerging market debt at BNP Paribas Asset Management in Singapore. The divergence in note prices also shows longer-term uncertainty over access to bilateral or multilateral financing sources, he said.

Sri Lanka’s credit rating was cut to CCC+ from B- by S&P Global Ratings on Friday. The credit assessor said the pandemic has significantly hurt the government’s capacity to generate earnings through sectors such as tourism.

The government said it was “disappointed” with the rating action, which has ignored the positive developments that will result from proposals presented in the 2021 budget with regard to fiscal consolidation and deficit financing.

“S&P, in its medium term projections, grossly overstates the level of fiscal deficit and the external deficit of the country,” it said in a statement late on Friday.

The finance ministry said last month that the country will engage with investment and development partners and implement necessary measures to build up reserves through non-debt creating inflows. Gross official reserves are expected to improve to around $6.5 billion by end 2020 on expected swap arrangements and term financing from the China Development Bank in December, it said.

But a recovery in imports, while tourism earnings remain stalled with international borders shut, could swell the current account deficit next year, the Institute of International Finance said in a report this week.

“Funding for current account deficits and bond amortization depends crucially on official financing, as market access looks unlikely,” it said.

In recent months, Sri Lanka’s credit rating was cut also by Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings, even as the government in October repaid a $1 billion international bond out of its foreign exchange reserves.

Sri Lankan authorities have pushed back on the longer-term concerns. Central Bank Governor Weligamage Don Lakshman said last week that “fears surrounding Sri Lanka’s debt sustainability appear unfounded,” amid the island nation’s adoption of a fiscal consolidation path from 2021, and the increased emphasis on domestic debt to finance budget deficits.

“Perhaps the one saving grace for bondholders, especially the ones with more immediate maturity, is that the government has publicly reiterated that the government has no plans to default and has never defaulted,” analysts at Citigroup Inc. led by Johanna Chua wrote in a report this week.

(Bloomberg)